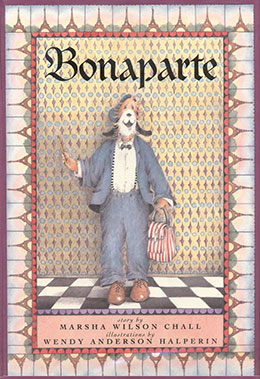

Bonaparte

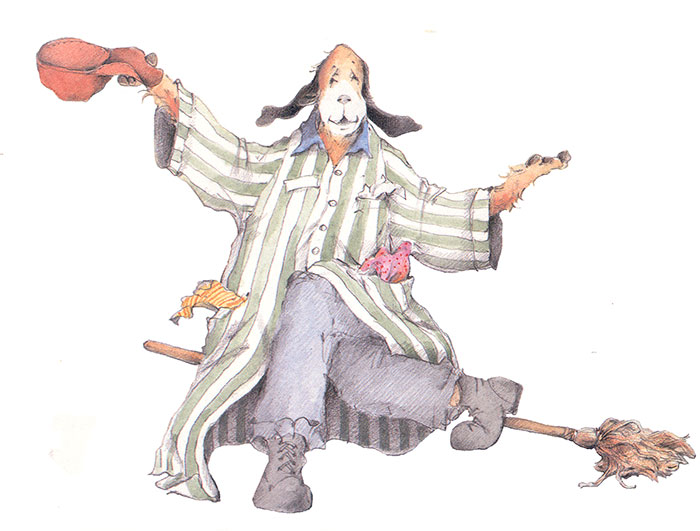

What’s a hound who misses his boy to do? Bonaparte is devastated. His boy, Jean Claude, has been sent away to La School d’Excellence. And the first rule is no dogs allowed. But Bonaparte is determined to see his beloved Jean Claude again. Perhaps they’ll believe he’s a student or a drummer in the school band or a lunch lady. With magnificent drawings, full of details to discover with each new reading, Bonaparte is a cold-nosed, warm-hearted tale.

Awards and Recognition

Smithsonian Notable Book for Children, 2000

Parents’ Choice Silver Honor Award, 2000

Minnesota Book Award Finalist, 2001

Resources

- The story takes place in Paris. Take a tour of the city via photos at this website.

- Make a list of other disguises Bonaparte could use to try and get into the school.

- Use a stamp to make a patterned design around the edge of white paper and draw a picture of Bonaparte. (Look at the cover)

- Write about the changes we would have to make if we allowed all of the students to bring their dogs to school.

Thanks to Kathy Johnson, media specialist in Alexandria, Minnesota, for these suggestions.

Marsha writes:

I wrote Bonaparte for at least two reasons. First, I was (and still am) an only child. Second, my earliest peer was a dog. Please follow the syllogism: Brothers are boys. Buff, a dog, was my brother. Therefore, Buff was a boy. Logic aside, dogs and boys do indeed have much in common: they’re messy, drool a lot, and smell bad sometimes; they also perform terrific stunts, make fascinating sound effects, and are great chums all around.

Of course, dogs, like boys, can talk when they must and are probably capable of many mysteries in their secret lives. When my father, my kids, and I picked up my second brother, Hank (who remarkably resembled my older brother, Buff), my dad already had his eyes on the prize—Best in Show. Hank came with papers and was pedigreed, sired by a champion. But I didn’t care about his lineage. I just wanted him to stop shivering long enough to learn to go on the paper and settle in with his new pack.

Too young to compete, Hank slept through most of his first dog show—1,900 Canadian and American dogs on parade at the Lake Minnetonka Kennel Club All-Breed Dog Show. I was deeply satisfied. I didn’t want Hank to go to the dogs, especially those dogs. He was one of us, not them. Hank was real.

I wrote Bonaparte first for Hank. In the earliest drafts, Bonaparte, a dog corrupt with braggadocio, lured Jean Claude’s companionship with florid displays of talent—in ballet, in paleontology, in cooking French delicacies—like the dogs at the show. But Hank didn’t get it.

I wrote Bonaparte first for Hank. In the earliest drafts, Bonaparte, a dog corrupt with braggadocio, lured Jean Claude’s companionship with florid displays of talent—in ballet, in paleontology, in cooking French delicacies—like the dogs at the show. But Hank didn’t get it.

I couldn’t either. The story never worked until I finally wrote it for myself. What mattered to me was Bonaparte’s sincerity, his dogged determination to be with his boy.

At the end of the book when Bonaparte sheds his last disguise, saying to the Regents, “Perhaps you need a good dog,” he has finally found himself. He is a dog—no more, no less. At his best as himself, he naturally finds his boy.

At the end of the book when Bonaparte sheds his last disguise, saying to the Regents, “Perhaps you need a good dog,” he has finally found himself. He is a dog—no more, no less. At his best as himself, he naturally finds his boy.

I write my best when I write to find myself, my true fears and dreams. In this story, I rediscovered my need for connection, to be part of the pack. In Bonaparte, I found a heart familiar with my own. C’est bon!

Reviews

Fresh as a newly baked croissant, this delightful confection finds a lonely pooch longing for his young master’s warm lap and “determined to find his boy” after Jean Claude is sent off to boarding school. Sadly, “La School d’Excellence” has a strict policy: “NO DOGS ALLOWED.” This doesn’t deter Bonaparte, however, who sniffs out Jean Claude’s trail. Halperin’s (Sophie and Rose) charming pencil and watercolor panel drawings chronicle the canine’s route through the breathtaking streets of Paris, with its cafés, fountains and fruit stands (one heartbreaking vignette shows the furry fellow sleeping “on a pillow of stone” at the foot of a statue), until he storms the school’s gates. He arrives daily in a different disguise as the boy’s mother, he’s twigged when he offers the registrar his dog license as I.D.; as a new drummer in the high school band, his tail (which wags “in four-quarter time”) gives him away. The day Bonaparte turns up as the new janitor, his canine talents are finally appreciated: Jean Claude is discovered missing and it’s up to Bonaparte to track him down. Chall’s (Rupa Raises the Sun) narrative strikes just the right balance between humor and feelings of loss in this captivating dog-loses-boy, dog-gets-boy tale. Her words together with the artwork’s elaborate borders and delicately detailed drawings will waltz straight off the pages and into the reader’s hearts. (Publishers Weekly, starred review)

Bonaparte, a shaggy dog, misses his school-bound boy so much that he ventures from their village to Paris for a reunion. Unfortunately, La School d’Excellence has a “no dogs allowed” policy that hardly deters the clever canine from donning guises to gain entry. Though barred at every turn, he and Jean Claude eventually connect and even affect change at the stuffy school. The language in this well-told story stretches readers’ imagination—“Alone that night on a pillow of stone, Bonaparte longed for the warm lap where he’d sprawled, lumpy and baggy with ease.” Every page is bordered by a unique and sometimes elaborate pattern. This frame is then subdivided into sections. Within each one, a pencil-and-watercolor image embellishes the plot. All text is housed within its own dialogue box on every page. Readers will pore over the details in the pictures, panel by panel. Love conquers all in Bonaparte. (School Library Journal)

The quick-witted Bonaparte will not be denied. Separated from his master, Jean Claude, whose new school does not allow dogs, Bonaparte determines to gain entrance. Each weekday he appears at the school. On Monday, he comes as himself, a loyal dog, “to fetch my boy.” His ruses become more desperate as the week progresses: Tuesday, Bonaparte dissembles as Jean Claude’s mother; Wednesday, as another candidate for entrance to the school; Thursday, as a drummer for the school band; Friday, as the new lunch lady. On Saturday, disguised as the new janitor, Bonaparte discovers Jean Claude missing from school. Wily readers will know instantly what’s up and where it will all end, but that only adds to the pleasure of this light-hearted story. Halperin’s detailed pencil-and-watercolor illustrations, dominated with pastel tones of pinks, lilacs, and blues, re-create the France of cafés and chateaux, of art galleries and carousels. Each page is bordered with motifs in a French spirit: repeated cathedral doors, stained-glass gothic windows, church spires, bridges, and walled cities; the cover’s border of dawn-lit Eiffel Towers initiates the winning pattern. But the real winner is Bonaparte himself; however garbed, whatever chapeau, Bonaparte est charmant. s.p.b. (The Horn Book)

The Bonaparte of the title is a whiskery lop-eared canine, bereft when his owner, young Jean Claude, goes off to La School d’Excellence for his education. The faithful pup follows his master’s trail, but when he addresses himself to the school, he’s informed that they have a strict anti-dog policy. Refusing to take this proscription lying down, Bonaparte disguises himself variously as Jean Claude’s mother, an entering student, a player in the band, a lunch lady, and a janitor, each time getting found out as a dog; on his last unmasking, he discovers that Jean Claude is missing, and the school shifts to support of loyal Bonaparte as he finds their errant pupil. The high-spirited comedy (kids will particularly appreciate Bonaparte’s reasoned conversations with the school authorities) offsets the slight preciousness of the faux-French fillips; the dog-boy friendship and the eventually happy doggy school (the “No Dogs Allowed” sign changes to “Now Dogs Allowed”) are warm and delightful components. Halperin’s art employs its customary borders containing precise and petite motifs accenting the larger images, which often separate into sequential panels that support or add action to the central scenes; text is tightly controlled in boxes that float through the illustrations. Jean Claude and Bonaparte, both—especially the latter—personable figures, keep the pale intricacy of the visuals from becoming chilly and distant, so the result is an inviting and Anno-like complexity of landscape. Use this to add a little oh-la-la to a doggy readaloud. (The Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books)

Incroyable! What’s a dog to do when his young master is sent to boarding school? Track that child down, of course, which is why Bonaparte, one tireless canine, happens to be prowling the streets of Paris. Utterly, well, fetching. (Smithsonian Notable Books for Children)

illustrator, Wendy Anderson Halperin

DK, 2000

ISBN 978–0‑78942–6178

ages 4 and up

32 pages

Look for this book at your favorite library or used bookseller.